|

Promotion of Waste Exchange Systems: Five Models from Bandung, Indonesia

Abstract:Contents

1. Introduction

Sustainability in all the dimensions of its definition - eoconomic, social and environmental - needs to be at the core of all the decisions we take on a daily basis. Promotion of more sustainable patterns of consumption and production, particularly aimed at private sector companies, is an approach that enables them to develop and adopt policies and practices that are cleaner and safer; make efficient use of natural resources; ensure adequate management of chemicals; incorporate environmental costs; and reduce pollution and risks for humans and the environment.

But aspirations for a high quality of life, and high rates of resource use have had a unintended and negative impact on the urban environment: generation of wastes far beyond the handling capacities of urban governments and public utilities. Companies are therefore grappling with the problems of high volumes of waste, the costs involved, the disposal technologies and methodologies, and the impact of wastes on the local and global environment.

Most companies have, time and again, identified waste management as a major problem. We can observe three key trends with respect to industrial waste - increase in volume of waste generated by companies; change in the quality of waste generated; and the disposal method of waste collected. But these problems have also provided a window of opportunity for companies to find solutions - involving the community and the private sector; involving innovative technologies and disposal methods; and involving behaviour changes and awareness raising.

2. Waste scenarios in the Private Sector

Waste is any surplus material generated from a process that does not form part of the final product. Industrial wastes has two issues we have to contend with - (a) the amount of waste produced is a consequence of the quantity and quantity of materials consumed and efficiency with which it is produced, and (b) once waste has been produced, dealing with it has an impact on the environment that should be minimized.

The characteristics of industrial wastes are different from that of household or other wastes. Industrial wastes are predominantly homogeneous (and not mixed as with household wastes) allowing for easier reuse and recycling. Depending on the waste type and manufacturing process, industrial wastes are produced either regularly or are one-time wastes. Some wastes could also contain hazardous components that require special and separate handling.

Most industrial wastes are landfilled - however this is not only harmful to the environment but due to waste disposal and landfill costs, it is becoming increasingly expensive.

As a first step, through resource efficiency, waste prevention, and emissions reduction at source, organizations can maximize output and increase profits. Waste minimization calls for the systematic reduction of all forms of waste and may include energy, water, materials, effort and process and production waste in order to conserve resources. This can be achieved through different approaches such as better product design and material efficiency ("Design for Environment"). Companies have also implemented strategies to design their products to be easily dissembled and recycled ("Design for Disassembly"). Others have attempted better and more efficient manufacturing processes, better packaging that use less materials, and product buy-back systems that facilitate higher rates of recycling.

Rubbish and waste can account for over four percent or more of a business' turnover. Due to these disposal costs, (including storage costs in some cases) and of any additional costs arising from potential pollution, degradation or accidents, companies are increasingly looking for comprehensive waste management approaches that can overcome these shortcomings.

Of particular interest are approaches that enable reuse and recycle of wastes and by products. Waste exchange systems fall in this category. By providing a business reuse network, waste exchange systems help prevent usable materials from becoming waste.

3. What is a waste exchange?

A Waste Exchange is an operation that enables materials discarded by one company to be re-used by another company. These can be scrap, production by-products, obsolete or unused raw materials, hazardous waste and recyclable products.

The potential cost savings that can be made are immense as on average businesses spend 4.5 percent of their total turnover on waste disposal and a significant percentage on raw materials. Many of these costs can be eliminated through exchanging materials, turning what was once a significant drain on financial resources into profit.

In general, a waste exchange system (also called a 'materials exchange' system) is an alternative to disposal of waste to landfill. Such systems enable the efficient reuse and recycle of materials, reduction in waste that has to be disposed, cost savings in raw materials and waste disposal, and enables compliance with waste laws and regulations where relevant. For large companies (such as JFE Steel in Japan, illustrated in Figure 1), wastes also provides business opportunities to set up subsidiaries that utilize by-products from one process of the company to be used to create further new products.

Through a waste exchange system, companies can find alternatives to landfilling of unwanted materials, save on disposal costs and support community groups by registering re-usable materials. Through waste exchange, users can access re-usable materials, access information about local recyclers and regional recycling services or reduce rubbish going to landfill.

A quick survey of waste exchange systems established worldwide reveals four key functions:

The main function of a waste exchange system, of course is its Database function. In populating a database, the following points are usually collected. (See Annex 1 for another simple form):

4. Features of a typical waste exchange system

Most established waste exchange systems have a combination of of the following features -

5. Bandung's Economy

Bandung has undergone an intensive and impressive process of industrial and technological transformation in the past 20 years, with a more technology, skill and capital-intensive production processes.

Bandung like most major cities in the Asia-Pacific region has seen considerable growth in its urban population and industrial growth. It has attempted to implement a number of sustainability initiatives, such as a 3R Programme (Reduce, Reuse, and Recycle), targeting different stakeholders. But the growth patterns of its urban population and industrial clusters have resulted in unintended and unforeseen environmental impacts that will have to be addressed in the short and long terms.

As a result, Baundung city has strengthened its competitiveness by developing industry clusters that promote dynamic partnership between the government and the industry, and interlinkages between industries themselves. These policy directions provide an excellent opportunity to guide the industrial growth in an environmentally sound manner, using various sustainability concepts, such as waste exchange among factories.

The city of Bandung has adopted a policy approach to put environmental concerns in the forefront of the development of the city, and to create the necessary conditions to enable concerted action to be taken. An integrated approach that incorporates different sustainability ideas and concepts, enabling broader stakeholder collaboration, and reduce resource dependency, is to be put in place. This is being done within the scope provided by concepts such as 3Rs, and sustainable consumption and production patterns.

6. Survey of Industry in Bandung

In order to explore and expand on the above ideas, a survey of small, medium and large industries in Bandung City was carried out by Bandung's BAPEDA office, covering questions related to the products produced, raw materials used, and scraps/wastes generated by the factory/company. The potential uses of the scrap/waste, packaging for disposal, and other details of current practice was also asked.

An initial total of 17 industries were surveyed for the purpose. A brief summary of some of the responses is shown in the following table.

Industry Type Of Industry Type Of Waste Volume Category 1 Pt.

Bio Farma Immunization

Plant Ash

Of Animal Body 1 Ton/Day Hazardous 2 Pt.

Kimia Farma Pharmaceutical

Plant Skin

Of Kina Seed 8 Ton/Day Non

Hazardous 3 Pt.

Pindad Army

Factory Wet

Sludge 11 Ton/Year Hazardous Furan

Sand 20 Ton/Year Oil/Chemical 200 Drum/Year Mixing

Sludge 28 Drum/Year 4 Pt.

Paratex Mekar Textile Sludge 167 Kg/Month Hazardous Lestari 5 Pt.

Aneka Produksi Metal

Works Fly

Ash & Bottom Ash From Coal 62.5 Kg/Month 6 Pt.

Indosco Utama Metal

Works Fly

Ash & Bottom Ash From Coal 2400 Kg/Month Hazardous 7 Pt.

Grandtex Textile Fly

Ash & Bottom Ash From Coal 6000 Kg/Month Hazardous 8 Pt.

Indosinga Lestari Textile Wet

Sludge 2000 Kg/Month Hazardous 9 Pt.

Beteen Textile Textile Fly

Ash & Bottom Ash From Coal 20 Kg/Month Hazardous 10 Pt.

Perintex Textile Wet

Sludge 3750 Kg/Month Hazardous 11 Pt.

Ewindo Textile Sludge 12000 Ltr/Month Hazardous 12 Pt.

Cimuntex Textile Fly

Ash & Bottom Ash From Coal No

Data No

Data Hazardous 13 Pt.

Nagamas Textile Wet

Sludge No

Data No

Data Hazardous 14 Cv.

Banyumas Textile Sludge

From Coal 1250 Kg/Month Hazardous 15 Pt.

Omedata Electronics Sludge 10000 Kg/Month Hazardous Electronics 16 Sentosa

Makmur Gypsum

Gypsum

Sludge 60 Kg/Month Non

Hazardous Gypsum (Building

Material) 17 Tegep

Boots Leather

Boots Leather 8 Bag/Month Non

Hazardous

In order to demonstrate the viability of waste exchange and explore a more concerted approach to broader industrial waste management, a workshop meeting was organized in Bandung on 4 - 5 November 2007. The workshop included participants from a range of local stakeholders, including the local government, BAPEDA offices, research institutions and private sector entities.

A total of 23 persons participated in the meeting. The meeting saw presentations being made from four local companies (both large and small). As a part of the meeting, waste exchange case studies of two factories were presented to illustrate the viability of waste exchange among factories.

7. Waste Exchange Example 1: . Kimia Farma

Pt. Kimia Farma is a pharmaceutical company that produces the medicine quinine from Kina (or 'quina') seeds. It is one of the largest producers of quinine in the region, and supplies most of the needs for Indonesia and for other countries in the region. Quinine is the main medicine for the treatment of malaria, and has several other medical uses including digestive, fever and other health condition.

The quinine medicine itself is produced under very strict sanitary conditions from the bark and wood of the kina seed. The bark of the kina seed is first boiled and crushed in order to extract the base raw material from which quinine itself is synthesized and produced. The base raw material is produced in the form of crystalline blocks that is removed and further purified (in a second Kimia Farma factory). The remaining/resulting molasses is then allowed to drain in large brick and concrete tanks, before the pulp is dried and then disposed.

Initially, Pt. Kimia Farma disposed the residual kina seed pulp in the municipal landfill of Bandung, without any processing. But as production volumes increased, reaching the current levels of 8 tons per day, the company decided to explore alternative ways to reuse and sell the waste pulp.

Much of the residual pulp is wood-based and homogenous with little, if any, contamination or intermixing with other wastes types. The calorific value of the waste pulp was analyzed by an independent third party, and a value of about 2912 calories/gram was obtained (this is about one third that of ordinary coal). The sample analyzed also had 23.76% ash. Other constituents of the sample studied were as follows:

Pt. Kimia Farma participated in the waste exchange demonstration project with the help of local experts and Bandung city. As a result, it created compressed brickets from the pulp in order for them to be sold as fuel as an alternative to coal. The process consists of first drying the molasses in large tanks. The resultant dried pulp is then further dried in sunlight to reduce the moisture content. The dried pulp is then ground into a powder, mixed with clay that acts as a binder and then shaped into small balls using a 'ball shaping machine' It is further dried before it is packed and sold to factories in the area as a alternative fuel.

Most of these brickets are sold at Rp.100/kg to nearby factories that require fuel for furnaces etc.

The key lessons learnt from this demonstration exercise is the need for looking at the wastes/outputs resulting from manufacturing processes as a valuable resource. With a little value adding (drying, crushing and shaping the pulp into brickets), the 'waste' pulp was converted into a saleable product, which also reduced the dependence of the factories on traditional fuels such as coal, petroleum and electricity.

The factory did face barriers in the form of finding appropriate technologies to process the waste, in producing the right product from the waste (low moisture content + high calorific content of the brickets).

8. Waste Exchange Example 2: Pt. Pindad

Pt. Pindad is a metal processing factory in Bandung, producing a number of die cast manufacturing machines for other factories and industries.

The company is part of the Pt. Pindad Group, which is the largest and oldest arms manufacturing company in Indonesia. The factory initially used raw/pig iron for its production process.

But after consultation with a number of experts and collaborating in research with foreign companies and technology suppliers, it adopted a system that utilized a higher percentage of recycled and waste scrap metal in the casting process.

As result of this, and by instituting an enhanced waste exchange system in the city, the company now collects scrap iron from factories in the city and the neighbouring region, and has become a major user of scrap iron. The factory currently uses about 10-14% of its metal source from the reused/recycled scrap (amounting to about 8-10 tons per day) collected as a part of its waste exchange system.

Some of the key lessons learnt from the initiatives undertaken by the surveyed companies are listed below (shared during stakeholder meetings with local government officials, business leaders and academics in Bandung):

The case studies of industries surveyed in Bandung identified five models of waste exchange that could potentially be used for replication in other cities in Indonesia and elsewhere in the Asia Pacific region.

In this model, wastes generated from the factory's manufacturing processes are reused/recycled as-is within the same factory. This is most common in factories that generate single waste streams containing only one waste type.

Examples observed in the field surveys and visits included metals, glass or plastics reused once again in the factory.

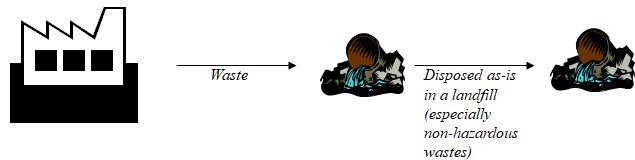

In this model, wastes generated from the factory's manufacturing processes are disposed as-is in a municipal landfill or dumpsite.

This is common for wastes that are mixed, or cannot be recycled. Most of such wastes are non-hazardous wastes in nature.

Examples observed in the field survey and visits included office wastes, garden wastes, and wastes from kitchens/canteens. Sometimes, wastes from gardens and kitchens were also composted and used in factory gardens.

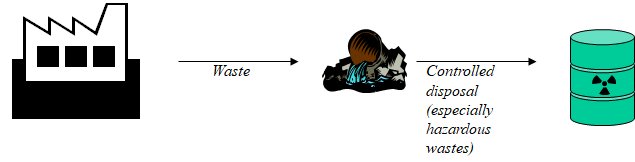

In this model, wastes generated from the factory's manufacturing processes are disposed in a controlled manner for processing. This is particularly the case for toxic or hazardous materials, where the waste was shipped to a hazardous waste processing plant for incineration.

Examples observed in the field surveys and visits included disposing of animal carcasses after testing, or certain kinds of ash/residues etc.

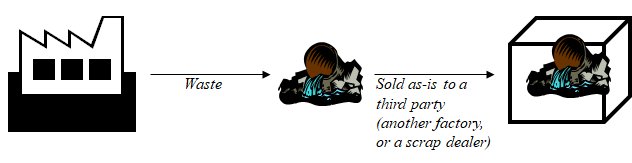

In this model, wastes generated from the factory's manufacturing processes are sold as-is to a third party essentially due to the fact that the wastes cannot be reused/recycled within the same factory. These third parties are usually other factories or designated / contracted scrap dealers.

Depending on the waste type, some wastes are also sold to informal sector dealers (for example, paper).

Examples observed in the field survey and visits included metal scraps, plastic and paper.

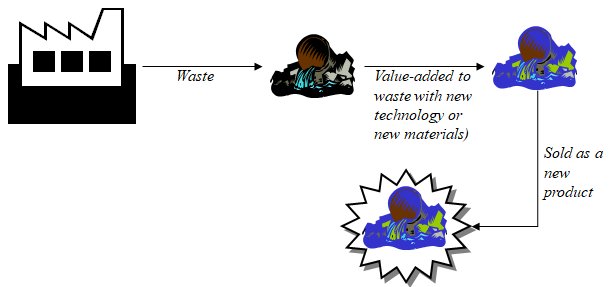

In this model, wastes generated from the factory's manufacturing processes are value-added to create a new product for sale, by the same factory or another factory/subsidiary.

Value adding is done with new technology and new materials, providing the maximum benefit of the wastes being generated.

Examples observed in the field survey and visits included the creating of burnable briquettes out of residual vegetative matter (after extraction of the quinine medicine) using clay as a binder, or creating art objects using cast away bottles and other glass items.

Annex 1: Sample (1) of an online waste exchange system

Sample form of a web-based online database to be filled in by companies that have waste materials to be disposed:

Sample form of a web-based online database to be filled in by companies in need of waste materials that is being disposed:

Web-based or computer-based databases of waste available or needed, can be searched. A typical database search window for waste exchange:

Sample search results page of a 'materials-wanted' listing:

Sample search results page of a 'materials-available' listing:

The goal of the Materials Exchange program is to reduce the amount of reusable business items going to landfills while assisting Minnesota businesses and organizations in obtaining free or low cost items and saving money. The Materials Exchange program is designed for materials that would otherwise be discarded. Below are examples of acceptable listings. All acceptable listings will appear on the Web site.

Acceptable Listings

Top 10 Most Frequent Materials Exchanged

Unacceptable Listings

For unacceptable listings, the Materials Exchange program will try to redirect listers to more appropriate venues.

Right to Reject

Materials Exchange reserves the right to reject any listing deemed inappropriate. The lister may be contacted by Materials Exchange if clarification is needed prior to approving a posting.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||